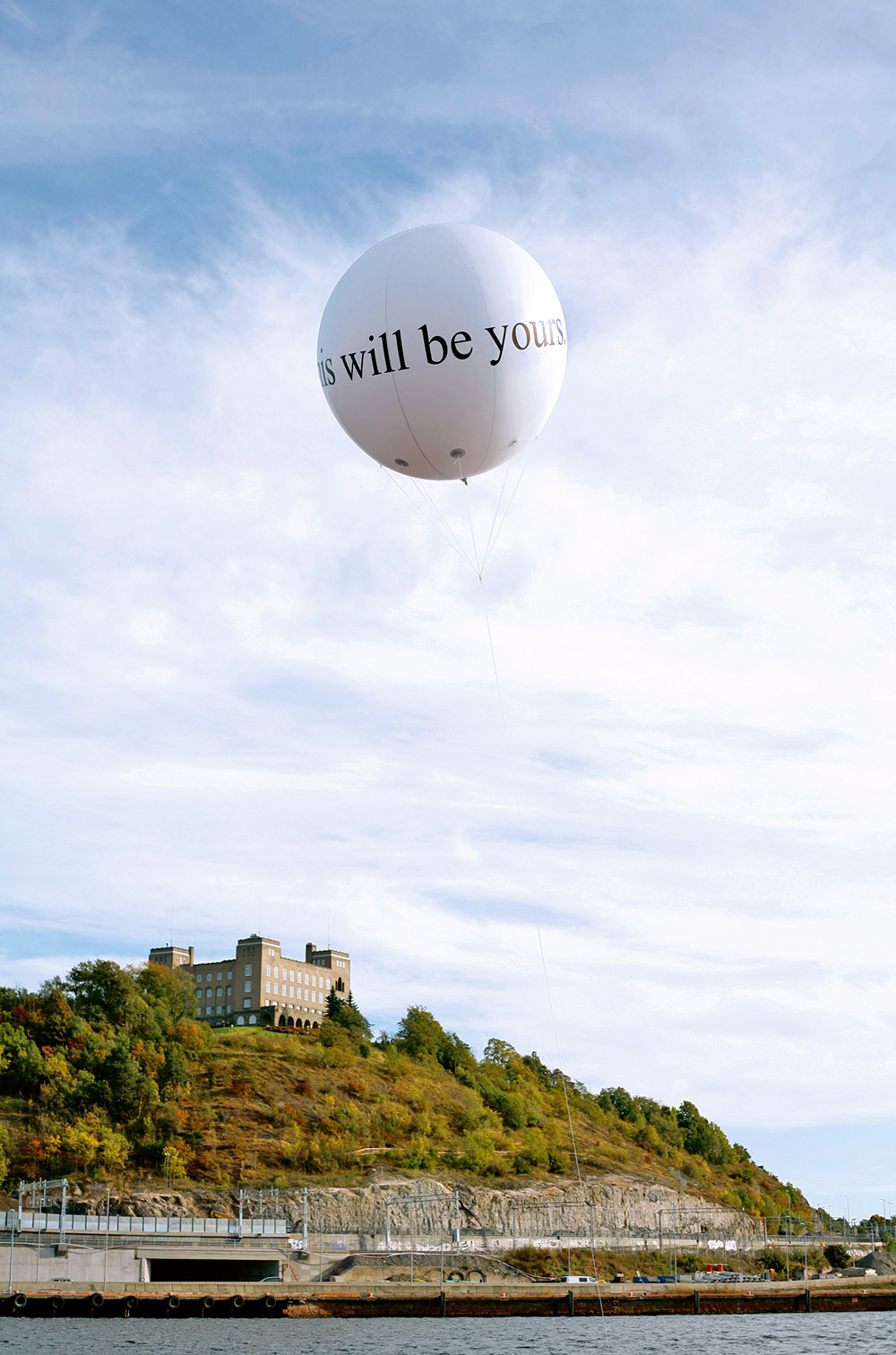

ONE FINE DAY, ALL THIS WILL BE YOURS.

Common Lands – Allmannaretten, Oslo

Marking the seven commons with a helium balloon. Temporary intervention in the urban development area Björvika, 2009/2010.

The development of waterfronts is a current trend in post-industrial cities where industrial harbor areas are being transformed into new urban spaces that emphasize mercantile, residential and recreational requirements. Common Lands - Allmannaretten is a one-year ongoing investigation into the context of the waterfront development of Bjørvika, the former harbor area of Oslo. The project started in 2009 and contains a series of commissioned art projects, seminars and workshops, accompanied by an online-reader.

In the planning and structuring of Bjørvika, the concept commons has been given great emphasis. Common Lands – Allmannaretten is an exhibition project that uses the process of redevelopment to highlight a number of issues associated with urban development, democracy, access to and the distribution of land. The project is curated by Åse Løvgren and Karolin Tampere.

Fortress Common – Festningsallmenningen

Akerselva Common – Akerselvaallmenningen

Station Common – Stationallmenningen

Kongsbakken

Lo Common – Loallmenningen

Opera Common

Opera Common

Station Common – Stationallmenningen

Snelda

Kongsbakken

Lo Common – Loallmenningen

Bispekilen

Kongsbakken

ONE FINE DAY, ALL THIS WILL BE YOURS.

COMMON LAND

If someone gave you the promise: “One fine day, all this will be yours”, would you trust it? Or would you insist on getting it in black and white?(1) On the future grounds of the newly developed district of Bjørvika in Oslo’s harbor area the land owners gave a promise. It is the warranty of free access to public space and communality connoted in the term allmenning: commons. Seven areas, drafted as seven fingers reaching from the existing city into the development area, are designated as common lands. Do you assume common land is for everyone? You’re wrong. Access and use equally conceded, free and uncontrolled? No way. Traditionally common land was subject to the ‘rights of common’, for instance, the right to graze stock, or to collect wood as a way to improve a sparse income. These rights were granted to specific individuals, the ‘commoners’, mostly living in certain properties, or in a certain area. Common land is the reverse side of private property, even more so: in feudalistic times it served as a sedative against the painful injustice of the privileges of aristocracy and was used to pacify insurrections, or allay wrath about unequal chances and unequal distribution of goods. Faded and diluted as these notions may seem in the context of a contemporary capitalistic city, it is still the utilization of space which determines its potential for public use. What could this use be in a post-industrial scenario where fishing, grazing cattle, gathering fruit, nuts, turf, reeds, roots, game, and so on seem out of place? Are we left with shopping as the last remaining form of public activity, as the architect Rem Koolhaas states?(2) Is drifting and drinking in the streets the only self-empowered action, as practiced by the Situationists in Paris in the 1950s? And if so, where does the demarcation line between accepted and deviant behavior run?

COMMON USE

In Bjørvika the modes of practice are inscribed into the blueprints of the commons. Even though the prose of the developer’s brochures avoids notions of exclusivity, the outlined repertoire of behavioral patterns syncopates the envisioned personnel as a socially homogenous group. The actors on the urban stage are pictured recreating, eating out, working out, attending major events and commercial activities, outdoor concerts and exhibitions, taking a tourist boat to the islands, anchoring in the guest marina, or simply enjoying a quiet moment.(3) Now, why the unease with the good will? Why the long face in light of ‘one of the most comprehensive urban development projects Norway has ever seen’, representing Norwegian identity ‘at the cutting edge’ of technology and culture, on a parr with international competitors?(4) Nationalistic undertones aside, the good intentions contradict experiences made with city development of a comparable scale in Berlin, Copenhagen or Hamburg, ensuing commodification and privatization of space with all the accompanying side effects of surveillance, disciplination and regulation. It raises the question how space is divided and distributed, how individuals and parties are positioned within and how they are conceded participation.

STAKING CLAIMS

Constructing claims land. In a clash over land, architecture can become a weapon.(5) Bjørvika will be a new city within the city on former industrial plots, traffic routes, inbetweens, wasteland, insignificant rest spaces. New structures will further densify the habitat. Cubature layout, street grids and the ensuing orientation and habitual everyday use of space constitute a ‘place identity’(6). Surfaces communicate cultural codes, regulate belonging and exclusion, grant or deny access. Glass or brick facades, wooden panels or concrete slabs, metal curtains or natural stone demarcate territories. Graffiti and tagging are strategies of appropriation indicating erosion of value and control. We do not picture public space as a playground of unlimited opportunities where the collective body frolics to its heart’s content. Public space is highly controlled, maintained, commodified and policed. Free access and use of the commons for all presume social equality and disregard the gap between those who have logos and take part in discourse and those who can only groan to utter their discomfort and pain.(7)

…

Annotations

1) As a promise given by the sovereign to his successor, by a farmer to his dutiful associate, or a father to his offspring, it sure is a paternalistic and patronizing thing to say. Its subtext reads: If you behave…—Or else… It is a disciplinating trope, extorting obedience, keeping the addressee on a tight rein. Law history holds plenty of cases of unkept promises and fooled believers.

2) “Through a battery of increasingly predatory forms, shopping has infiltrated—even replaced—almost every aspect of urban life.”, Rem Koolhaas in: Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. Chuihua Judy Chung (ed.), Cologne 2001.

3) Bjørvika—the new city within a city. Agency for Planning and Building Services, City of Oslo, 2008.

4) “The new district is to be the pride of all inhabitants of Oslo (…)”, Masterplan for Bjørvika, Bispevika, Lohavn, Oslo City Council, Aug 27, 2003. Cited in: Get to know Bjørvika—the new city within a city. Bjørvika Utvikling/Bjørvika Infrastruktur, Oslo.

5) Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, London 2007.

6) Bernhard Waldenfels, Ortsverschiebungen, Zeitverschiebungen, Frankfurt/M. 2009.

7) Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics And Philosophy, Univ. of Minnesota 1998.

aus: Dellbrügge de Moll, One fine day, all this will be yours. Libretto for Agonistic Encounters on Common Lands, Oslo 2010